In 1804, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were sent to find a route across the central United States to the Pacific, creating a pathway for the new nation to spread westward from ocean to ocean.

Flathead Indians

Sketches in William Clark’s diary show the practice among some Native American tribes of altering the shape of their heads by pressing their skulls during infancy.

Jefferson immediately commissioned a survey party to explore the new territory, as well as the unclaimed lands beyond the “great rock mountains” in the west. The hope was that a river route could be found to connect the Mississippi with the Pacific beyond the mountains, making it possible to open the land for settlement.

Expedition journal

A reproduction of William Clark’s diary shows the detail with which he documented the expedition. Thanks to his and Lewis’s observations, their adventure became a founding tale of the young United States.

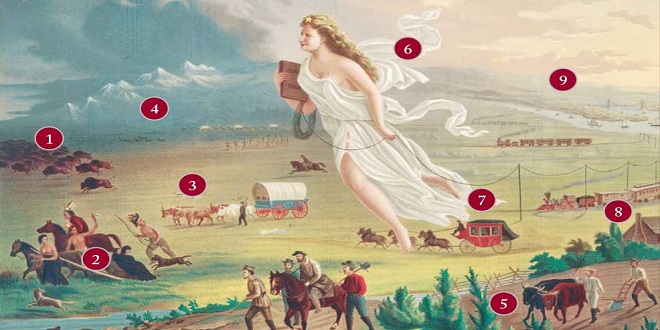

The Lewis and Clark expedition

Jefferson appointed his personal secretary, Meriwether Lewis, a man who combined learning with frontier skills, as expedition leader, and selected another frontiersman, William Clark, to help him. Together they assembled a team of 33 men, and in May 1804, this “Corps of Discovery” began to make its way up the Missouri River in a fleet of three boats. They traveled all summer until the first snowfall then put ashore and built a fort, Fort Mandan, in which they could wait out winter. These were potentially hostile lands, where no non-Native American had ever.

Ventured, so the expedition hired as an interpreter and guide Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian fur trapper, and his Shoshone Native American wife, Sacagawea. In spring 1805, when the ice on Missouri broke, the expedition resumed. In the last week of May, the party had its first sighting of the Rockies, the great mountains that it would have to cross. On June 13, it reached what Lewis described as “the grandest sight I ever beheld”—the Great Falls of the Missouri River, an obstacle that would take a month to pass.

At the foot of the Rockies, they encountered the Shoshone tribe, with whom they bartered for the horses necessary to cross the mountains. It was an arduous journey, during which the expedition had to resort to eating three of the animals. Eventually, they descended to the banks of the Clearwater River. The Rockies were behind them, the Pacific Ocean in front.

CONTEXT The Lewis and Clark Trail

Today, a series of marked highways, that mostly run parallel to the Missouri and Columbia rivers, serves as an official Lewis and Clark Trail. More in keeping with the original spirit of adventure is the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, which is part of the National Trails System and extends some 3,700 miles (6,000km) from Wood River, Illinois, to the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon. Administered by the National Park Service, it provides opportunities for hiking, canoeing, and horse riding.

Last word

The most unchanged part is the White Cliffs section of the Missouri River in north-central Montana, a protected area only accessible by boat. For Lewis, the sandstone formations here afforded “scenes of visionary enchantment.